Eddie Muller, prezident Film Noir Foundation a autor několika publikací o filmu noir, nám laskavě poskytl rozhovor, jehož anglickou verzi přikládáme. Český překlad je k dispozici na stránkách časopisu

25fps.

Could you briefly describe the purpose and various activities of Film Noir Foundation?

The Foundation was created to rescue and restore noir films that would otherwise be in danger of extinction. I wanted to make sure that there were still 35mm prints of all the films I loved, especially the independently produced films of the 1940s and ’50s that did not have a big corporation protecting them. Many such films can slip through the cracks. Joseph Losey’s The Prowler, for example, was a film known mostly through rumor and reputation, as it had only one deteriorating print to show for itself in this country. We found a fine-grain positive copy of the film at a defunct laboratory in Los Angeles and used it to recreat a new restored negative. So now there will always be an accessible print of that film. Our restoration was used as the basis of the recent DVD release, which received tremendous acclaim in 2011, both in the U.S. and France—because it brought one of Losey’s greatest films back into circulation.

In addition, we are trying to educate young people about the value of vintage films, so they won’t let all the new technology—3D and High-Definition and all that—prevent them from enjoying the classic storytelling in these older films, particularly noir. So when I present festivals in various cities, I also try to go into the schools, to impress upon the younger people how great these films are, and how they have influenced many of the films being made today.

How many people are working on Noir City Festival?

We try to keep the core very small, like a commando unit in the military; the less time you spend administrating things the more time you have to actually accomplish things. But having said that, we continue to grow, both the Foundation and the festival—which I must stress are two different entities. The Film Noir Foundation benefits from the largess of the NOIR CITY festival, but the festival is its own self-contained operation. We stage the festival with a core group of about six people and several dozen volunteers. And trust me, no one gets paid much. All the proceeds go to save the films!

What makes San Francisco the perfect "noir city"?

If you mean as a setting for film noir, it’s the town’s inherent sense of mystery, and how small it is. It’s also the last stop when you’re heading west across the United States—or the first stop when you arrive from the Far East. It’s always been a crossroads, a place when people come to find themselves and to lose themselves.

But as a film-loving city, it is I believe almost on a par with Paris. The success we have had with NOIR CITY could not have happened anywhere else in America. That’s because of the people here, and the majestic Castro Theatre, which is still a single-screen movie palace, seating 1400 people. The people here realize that this is something special, and they have embraced it. While many people in the U.S. now prefer to stay home and watch movies on their computers or big-screen TVs, the people in San Francisco, of all ages, still want to go out for a night on the town, the way people did back in the 1940s.

What film(s) from this year's program do you think can be best appreciated on the big screen?

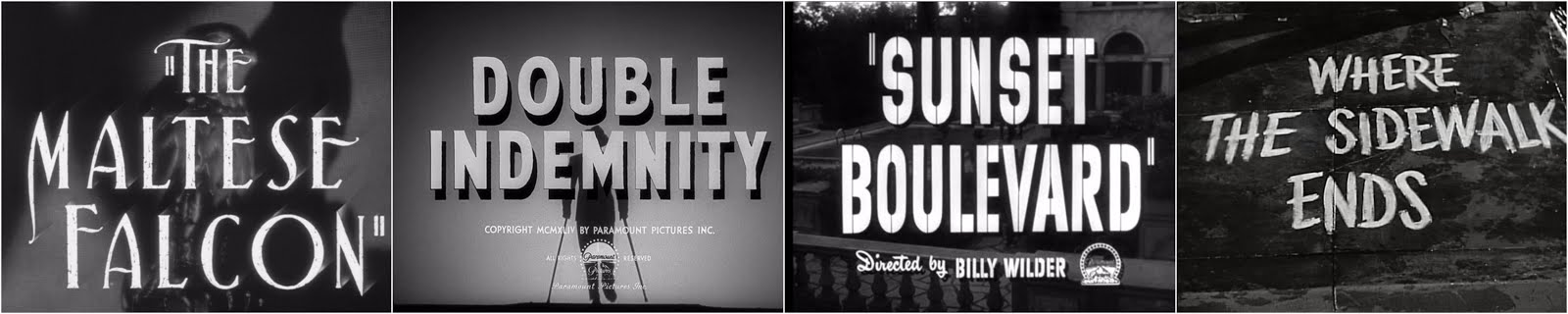

All of them! It’s the way they were made to be seen! It’s remarkable how much even an average film gains from being shown in a pristine print on a big screen. That’s why we always show a few familiar films, such as Laura, Gilda, and The Maltese Falcon alongside the rarities—people may know the films, but they may never have actually seen them on a big screen, in all their original glory. And I sadly have to tell people now that digital is becoming the standard for movie projection, that these screenings may be the LAST time they’ll have a chance to see a classic film projected in 35mm. As for favorites, I’m a huge fan of The Breaking Point (1950), and I’m thrilled that Martin Scorsese‘s Film Foundation, which restored the film, is giving us the chance to present the debut screening.

Being from the Czech Republic, we have a special weakness for Hugo Haas. What's your opinion of his films? What made you decide to include his Pickup in this year's program?

I think Hugo Haas is one of the great stories of American filmmaking in the 1950s. He is derided by serious critics, of course, but he figured out precisely how to maintain a career in Hollywood while satisfying his own urge to write, direct, and act. And the films are better than people realize! Pickup is good, so is Strange Fascination! Haas is unique, and a genuine auteur, which is a term so cavalierly applied to directors that it’s lost all meaning. Haas is truly an auteur. I don’t think he’s a genius, like Sam Fuller, another 1950s era auteur, but he’s much better than he’s usually given credit for.

What makes film noir so attractive to contemporary audiences? Why is it still—several decades after its heyday—so popular?

My own theory is that people now recognize that moment in the mid-20th century, the immediate postwar years, as the apex of American culture—and the moment that the culture also lost whatever innocence remained and began a downward slide. It feels like most of the culture’s greatest artistic and aesthetic accomplishments—in art, movies, literature, music, fashion, design, architecture—all reached a watershed level right about that time. But simultaneously, something was revealed, under the surface, that made us question our national identity. You see it in the politics of the times, in the contest for control of the public consciousness, in the fallout of the atomic bomb, in the rampant growth of consumer culture through the 1950s and beyond.

I don’t want to read too much into it, because I know for many people the love of film noir is very simple: they are compelling stories, wonderfully told. But for me, there is something more at work when I see the passion people bring to it. I believe there is a sense that we reached our peak back then: we looked better, we spoke eloquently, we had extraordinary style—but it wasn’t enough to keep us from self-destructing—and I think that’s the underlying ethos of noir itself.

And let me just say that it’s time for Prague to have a festival of American film noir! I was in Czechoslavakia in 1989, right at the time of the revolution, and it was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I haven’t been back since then, and I am very intrigued to see how it has changed. I traded dozens of American music tapes for the revolutionary posters created by students and I still have all of them, archived. Quite a collection. I had to take them out for another look when Havel died. I am finally about to watch The Fifth Horseman is Fear (1964), which is the only Czech film noir known at all in this country. If there are goood 35mm prints of it still available, I’d love to screen it in the U.S.